It often feels like inexorable forces are driving the Philadelphia 76ers toward disharmony — and eventually to the breakup of their star core.

Jimmy Butler, the newest star, popped off about the team’s idiosyncratic offense. The Sixers don’t run many pick-and-rolls because their best ball handler, Ben Simmons, practically refuses to shoot outside the restricted area. Joel Embiid conceives of the restricted area as his territory; he beat Butler to moaning about his place in Philly’s new three-star ecosystem.

Every time the Sixers lose a high-profile game — especially to Boston — there are calls across the media for them to trade Simmons. Embiid is the superior player. Philly has built its half-court offense mostly around him. Simmons’ lack of a jump shot becomes more of a liability in the postseason, when the game slows.

The young cornerstones do not complement each other, at least not as much as you’d like. They run about 4.5 pick-and-rolls between them per 100 possessions, about the same frequency with which New York busts out the dreaded Allonzo Trier/Mario Hezonja two-man game, per Second Spectrum tracking data. Both need more shooting around them. Butler wants to bulldoze to the rim, too.

After a blowout loss Wednesday to the Washington Wizards, the Sixers have now scored 105.7 points per 100 possessions in 366 minutes with Simmons, Embiid and Butler on the floor — about equivalent to Detroit’s 23rd-ranked offense, per NBA.com.

The Sixers aren’t worried — yet. A lot of those minutes have come with wobbly backups starting in place of Wilson Chandler and JJ Redick. The sample size is small. Lots of indicators — namely the team’s shot profile in those 366 minutes — suggest the three-star alignment is working better than that 105.7 figure would have you believe. All three are elite defenders when engaged.

The Sixers went into the Butler experience with eyes wide open, and still hope to re-sign him this summer, sources say. He objected during that recent film session only after coach Brett Brown asked if anyone wanted to add something — and after an assistant coach nudged T.J. McConnell to speak about his concerns, sources say. Butler didn’t mention just his own role; he mentioned McConnell’s too.

“When you ask the team, ‘What do you see?’ you’d better be prepared to listen,” Brown told ESPN.com. “I’m OK with it. I have to be. I am the instigator.”

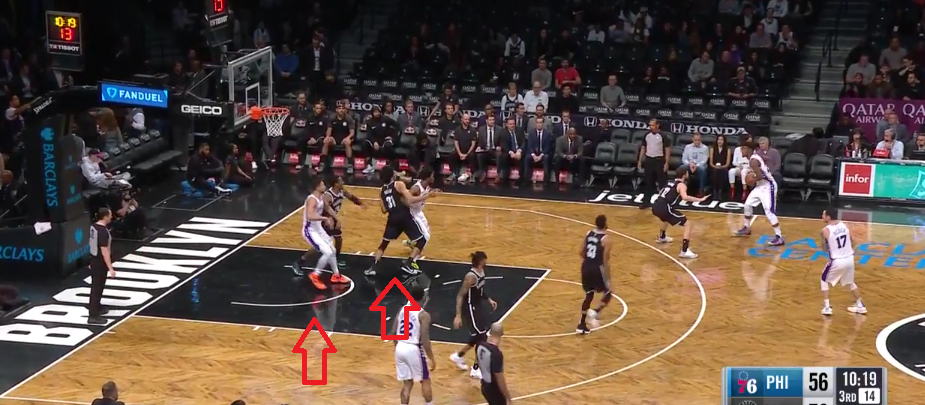

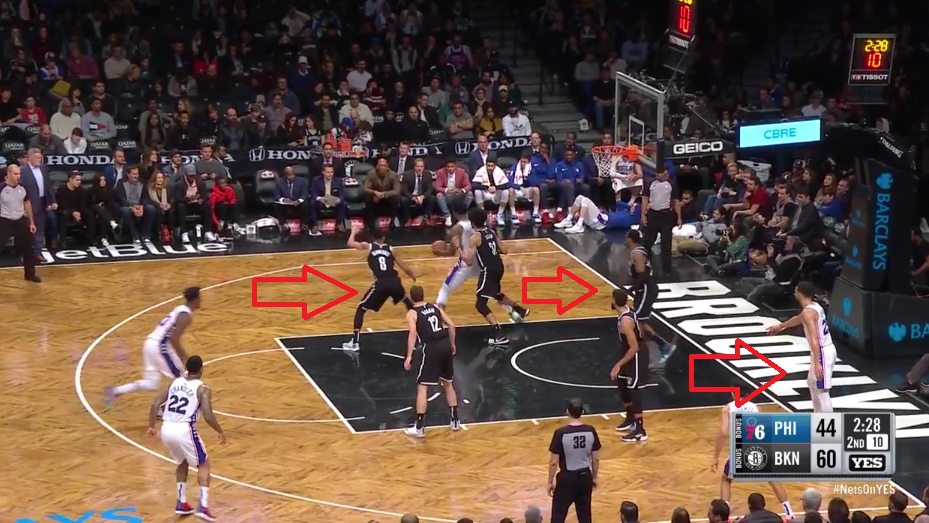

The Sixers know Embiid and Simmons are an awkward fit on offense. They know the history of young star duos portends a clash for control. They notice when two stars duck into the post at the same time, almost bumping each other:

They understand stashing Simmons in the dunker spot is an inelegant solution to getting him out of the way while Embiid posts up:

They feel the tension between a fast-break sprinter and a back-it-down bully. “That Ben is one of the three or four fastest players in the league — and that the game can sometimes just run past Joel — is both a blessing and a curse,” Brown says. “Joel needs the ball. This isn’t the 100-meter dash. Ben is getting better at recognizing that.”

Philly just got Butler, like, yesterday. Simmons has played 122 regular-season games. Philly is 18-9 since Butler suited up, and ranked eighth in points per possession. The Sixers’ healthy starting five is obliterating opponents by 15 points per 100 possessions — evidence that the stars work fine with legit starters around them.

All three have the talent and smarts to eventually wring more from what will always be an imperfect stylistic fit.

Embiid can trail fast breaks, grow into an average-ish 3-point shooter, and pump-and-drive past centers who can’t sniff his skill level. He touches the ball in the post about 12.5 times per 100 possessions when all three stars share the floor, per Second Spectrum. He gets more when Simmons is on the bench — about 19 per 100 possessions — but that 12.5 figure is on par with his pre-Butler average. It would rank sixth leaguewide. Embiid’s post game has not been marginalized.

Simmons and Butler are smart cutters who can post mismatches. Butler has hit more than 40 percent of his catch-and-shoot 3s over the last three seasons. The Sixers’ shot quality with all three stars on the floor is a hair higher than their overall average, per Second Spectrum; they feast in the restricted area. Three-star lineups have forced a preposterously low number of turnovers for reasons that are unclear and likely random. Toss in more easy transition points, and the numbers look different.

Still, there will be games when it doesn’t flow. Philly has scored more efficiently with any two of the threesome on the court, and the other resting, per NBA.com. Brown senses the strain of pleasing all three.

“I don’t enjoy feeling like a waiter — like I’m serving each of them food,” he says. “Although at times you have to be. Joel needs a touch. Ben needs to be posted. Jimmy needs a play. You hope the offense will dictate who gets shots, but it has been challenging.”

Butler has given up the most. He has finished only 18.7 percent of Philadelphia’s possessions when he plays with Simmons and Embiid — the usage rate of a role player. “At times, Jimmy doesn’t get the touches he needs,” Brown says. “That is true.”

Tough. This is usually how you win championships: join three great players, and figure out who needs to sacrifice what, and when, to beat top teams. The Warriors spoiled us into thinking that process is clean and easy. They are an anomaly, blessed with three of the greatest shooters ever — guys who remain useful and comfortable (to varying degrees) off the ball.

If Butler wants to run 50 pick-and-rolls per game, he should ask Kemba Walker about one-star purgatory.

Simmons thrived as a solo drive-and-kick star down the stretch last season, guiding Philly to 10 straight wins with Embiid injured. That run came mostly against bad teams. How would a Simmons-and-shooters team do in the postseason? (In that sense, the playoffs will be a fascinating test for the Milwaukee Bucks. Khris Middleton and Eric Bledsoe are too good to label the Bucks merely “Giannis-and-shooters,” but the gap between Milwaukee’s best and next-best players is larger than that of a typical championship team.)

Fit isn’t everything. You need a baseline of top-level talent to compete for titles, even if that talent overlaps. These Sixers hinge on how willing each of Simmons, Embiid, and Butler is to spend snippets of every game as Chris Bosh.

“I constantly remind all three of them: You do not always get to win on your terms,” Brown says.

Bosh was a perennial All-Star entering his late 20s when he became the third wheel in Miami. Big men make more natural third wheels; they don’t initiate possessions, and find offense screening for wheels Nos. 1 and 2.

Butler is the most natural analog to Bosh in terms of age, but he’s not a big man. Embiid and Simmons are in their early 20s, eager to establish dominance. Maybe inexorable forces — age and time — really are working against Philly.

But what are the Sixers supposed to do? You don’t shop for superstar talent at some player grocery store. You take what you can get, when you can get it.

For now, Philly mitigates fit issues by staggering minutes. Each star logs over 30 per game even while the trio gets only about 17.

Substitution patterns have worked against Butler playing the ball-dominant role he might crave. Embiid and Redick are so good together, Brown has them tied at the hip. He prefers to keep one of Simmons and Embiid on the floor. That naturally means more of Butler-Simmons without Embiid, and less Butler-Embiid without Simmons — an alignment tailor-made for Butler-Embiid pick-and-rolls.

There is plenty of time to engineer more of that. Brown has found some extended spots for it. Meanwhile, the team is coaxing Simmons into trying midrange jumpers. The long 2 is out of fashion, but Simmons being able to hit it when guys duck under picks would introduce more organic flow. The shot clock lasts only 24 seconds; you aren’t guaranteed a better look against postseason defenses.

Simmons has run only 11.7 pick-and-rolls per 100 possessions this season, a steep drop from his average — 26.2 — last season, per Second Spectrum. That isn’t enough. At the same time, he’s posting up and working as the screener in pick-and-rolls a bit more. He and Butler have a nice two-man chemistry.

Simmons should screen more often for Butler, Redick, and even Embiid in random semi-transition situations. If he rounds out his game, Simmons will chip away at some of the fit incongruences.

But they will always be there, and the playoffs will test them. In that setting, Philly will need to stretch the three-star minutes beyond 17 per game. They need it to work.

The calls to trade Simmons for multiple shooters will not stop until the Sixers advance to at least the conference finals. I’ve even seen it suggested Philly deal Simmons to Minnesota to get Robert Covington and Dario Saric back.

Those guys are good. But it is really hard to overstate how much talent — raw, supernova talent — you need to win at the very highest level. You know who looked worse than Simmons against Boston in last season’s playoffs? Covington. Shooting is one talent, but it is not on its own a capital-T talent.

Trading Simmons for complementary shooters also amounts to betting the franchise on Embiid’s continued health. Philly isn’t ready to do that, and shouldn’t be.

If you dreamt up a Simmons-for-multiple-shooters deal, you might land upon a pairing like Gary Harris and Jamal Murray — 3-point gunners who make plays off the bounce. Even if Philly would flip Simmons for those two — and they wouldn’t — Denver isn’t risking this season’s good vibes to see what a Simmons-Nikola Jokic pairing looks like.

And remember: Every discussion about dealing Simmons for shooters and playmakers is really a discussion about Markelle Fultz. Fultz was supposed to be the shooter-playmaker to meld everything. Instead, he is a zero. The Sixers coughed up a pick — Sacramento’s 2019 first-rounder — to move up for Fultz. Keep it as trade ammo, and perhaps the Sixers could have nabbed Butler without losing both Covington and Saric.

Depth is the Sixers’ biggest current problem. There may be more depth coming. Jonah Bolden has been solid. There is still hope within the team that Zhaire Smith may return this season. The buyout market looms. Philly will have cap space again this summer.

For those eager to deal Simmons, finding a two-man package as young, talented, and plug-and-play ready as the Murray/Harris duo is almost impossible. You veer quickly into “dollar for three quarters” trades. If the Sixers ever reach the point of investigating Simmons’ trade value, they should look for one youngish blue-chipper and some minor supplementary piece.

Even if you could construct such a deal that makes sense for both teams, executing it would require each to simultaneously feel ready for a franchise-altering shakeup. Blockbuster synchronization is rare.

Some non-Anthony Davis examples that fit the template:

• Simmons to Washington for Bradley Beal. Beal would not represent enough return for Philly. He’s three years older than Simmons, two years from his third contract. Simmons is on his rookie deal. Philly would demand more, and Washington would get queasy. You run into this valuation disconnect again and again.

• Simmons to Phoenix for Devin Booker. Booker is actually younger than Simmons. Philly likely demands enough additional stuff to turn Phoenix off.

• Simmons to Portland for C.J. McCollum. McCollum is five years older than Simmons. Ask for Zach Collins and a first-rounder, and the Blazers say bye-bye unless they are ready to exit the Damian Lillard era.

• Simmons to Charlotte for Walker, Miles Bridges, and an unprotected first-round pick. Interesting, but Walker is about to sign a massive contract at age 29.

• Simmons to the Clippers for Tobias Harris, Shai Gilgeous-Alexander and an unprotected first-round pick. This probably makes both teams a little uncomfortable. The Clippers love SGA. Harris likely isn’t enticing enough as a centerpiece for the Sixers.

• Simmons to Utah for Donovan Mitchell. Spicy! If Simmons and Embiid struggle with pick-and-roll chemistry, how would Simmons and Rudy Gobert manage? Philly likely demands a sweetener anyway.

• Simmons to Sacramento for … who? The Kings aren’t trading both De’Aaron Fox and Buddy Hield. Any other combination of Sacramento assets probably isn’t getting it done.

• Simmons to Chicago for Lauri Markkanen, Kris Dunn, and another asset. Dunn is 2½ years older than Simmons, with a blah NBA track record. Markkanen has played 86 games. Is he even old enough for election to the Bulls Leadership Council? I’m super high on him, but you couldn’t blame Philly for having questions today about his ceiling.

• Simmons to Indiana for Victor Oladipo. Oladipo is really good. He was better than Simmons last season. Simmons has a chance to be all-time good. That has to hold some appeal for an Indiana franchise that has — admirably — not drafted above No. 10 since 19-freaking-89. But the Pacers are happy where they are. Philly likely (again) demands something more.

• Simmons to Miami for Justise Winslow, Josh Richardson, and at least one unprotected first-round pick. Winslow’s surge has been one of the biggest under-the-radar stories of the last month. If he’s really this good, Miami’s trajectory looks different. But Philly isn’t doing this.

• Simmons for Luka Doncic. Ha. Never happening. You wouldn’t blame Philly for calling, though, right?

The Sixers have time to play this out, even after the Butler trade accelerated their timetable. Simulate the next five seasons of Sixers basketball a thousand times, and a lot of simulations would include the Sixers trading Simmons. Stars are traded toward the end of their second contracts all the time. The fit issues are real.

But that is one outcome among many. In the interim, a dozen events could shift the odds against it: another Embiid injury; a home run draft pick; nailing free agency; an out-of-nowhere trade that boosts the roster around them; injuries, trades, and free agency defections among their Eastern Conference rivals; a championship.

Yeah, that last one, too. It could be in play for this core. Right now, in early 2019, at the halfway point of Simmons’ second season playing in the NBA, two things can be true at once: The Sixers can win a championship at some point with Simmons, Embiid, and Butler; and the Sixers may come to a realization that they need to trade Simmons during his prime.

The possibility of the first thing is why you don’t rush the second.